Energy-saving strategies for hydrogen compressors: three ways to reduce operating costs

In the wave of the global energy structure transforming towards a clean and sustainable direction, hydrogen energy, as a clean energy with great potential, is increasingly attracting widespread attention. From fuel cell vehicles to industrial applications, hydrogen is regarded as a key component of the future energy system with its zero emissions and high energy density. However, the production, storage and transportation of hydrogen, especially its compression process, are often accompanied by significant energy consumption. As the core equipment in the hydrogen energy industry chain, the energy efficiency level of hydrogen compressors is directly related to the economy and competitiveness of hydrogen energy. High operating costs, especially electricity consumption, are one of the important factors restricting the large-scale application of hydrogen energy. Therefore, in-depth exploration of energy-saving strategies for hydrogen compressors and reducing their operating costs play a vital role in promoting the healthy development of the hydrogen energy industry.

This article will focus on the energy-saving optimization of hydrogen compressors and elaborate on effective methods to reduce operating costs from five key aspects. These five strategies cover the entire life cycle management from equipment selection, system optimization, operation management to technology upgrade and maintenance, aiming to provide comprehensive and feasible energy-saving guidance for practitioners in the field of hydrogen energy, in order to achieve the greening of the hydrogen energy industry chain and maximize economic benefits.

Working principle and energy consumption of hydrogen compressors

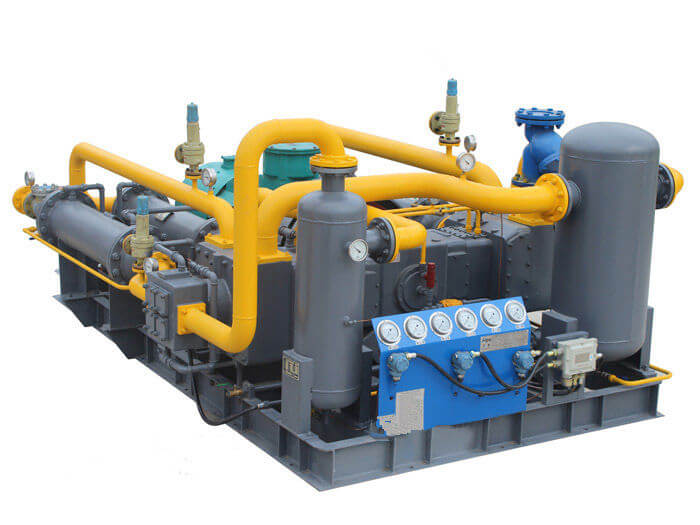

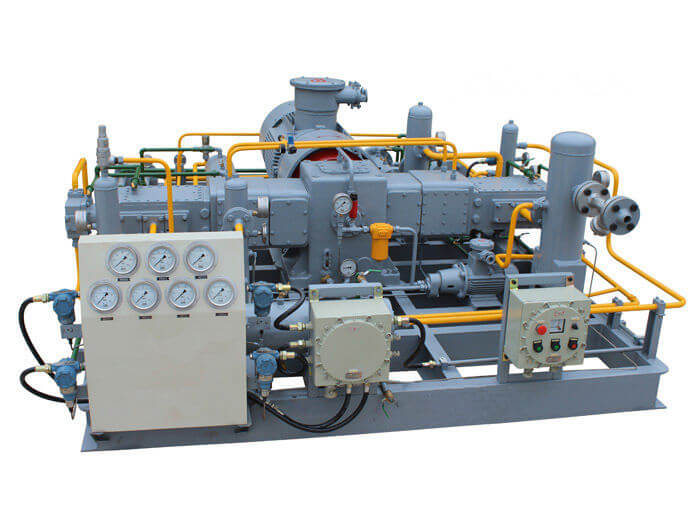

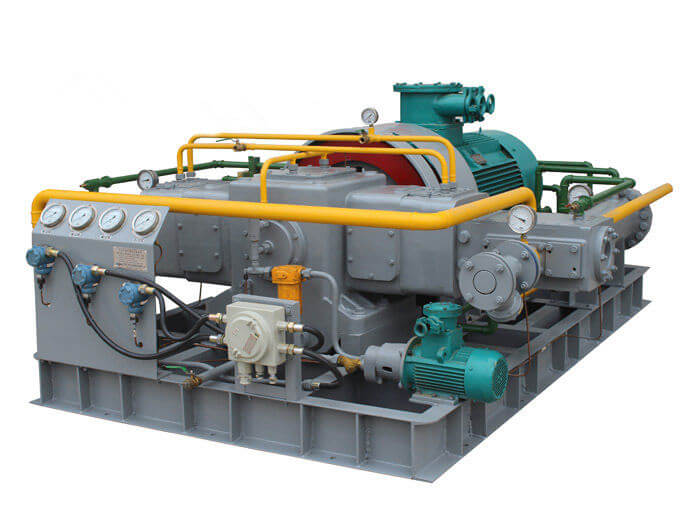

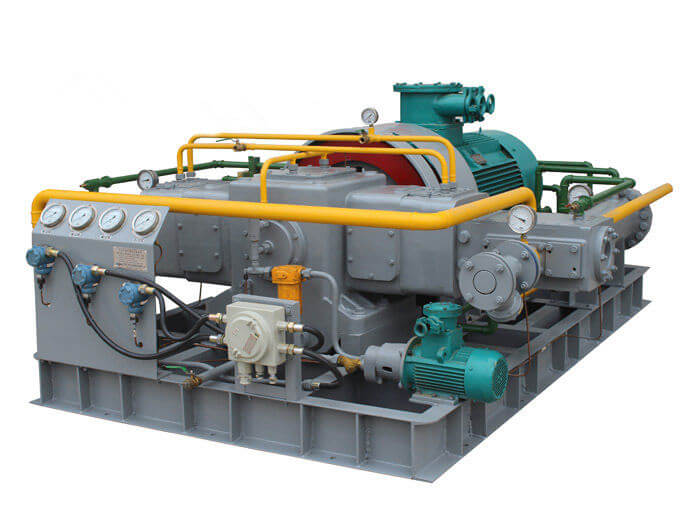

To understand the energy-saving strategy of hydrogen compressors, we first need to have a clear understanding of their working principle and the source of their energy consumption. The main function of hydrogen compressors is to increase low-pressure hydrogen to high pressure to meet the needs of storage, transportation or specific applications. According to different compression principles, common types of hydrogen compressors include piston compressors, diaphragm compressors, ionic liquid compressors, liquid ring compressors and turbo compressors.

Common types of hydrogen compressors and their working principles

Piston compressors: This type of compressor changes the cylinder volume by the reciprocating motion of the piston in the cylinder, thereby achieving the intake, compression and discharge of hydrogen. Its advantages are simple structure, easy maintenance, and suitable for various pressure ranges, but there are usually problems such as pulse flow, vibration and noise.

Diaphragm compressor: Diaphragm compressor compresses gas by driving the diaphragm to reciprocate through hydraulic oil. Since the diaphragm completely isolates the cylinder from the piston, oil-free compression of high-purity hydrogen can be achieved, avoiding contamination of hydrogen by lubricating oil. This makes diaphragm compressors dominant in applications such as fuel cells that require extremely high hydrogen purity. Its disadvantages are relatively small flow and high maintenance costs.

Ionic liquid compressor: Ionic liquid compressor uses ionic liquid as a compression medium to achieve hydrogen compression through the volume change of ionic liquid. Ionic liquid has the characteristics of low vapor pressure, non-flammable and non-toxic, which can effectively avoid hydrogen contamination and leakage. This new compression technology is still under development, but has good application prospects, especially in the field of high-pressure hydrogen compression.

Liquid ring compressor: Liquid ring compressor produces liquid rings through the rotation of the impeller, and the space between the liquid ring and the impeller forms a series of chambers with changing volumes, thereby achieving gas inhalation and compression. This compressor has a simple structure, stable operation, and is insensitive to impurities in the inhaled gas. However, liquid ring compressors are usually suitable for lower compression ratios, and liquid ring media (such as water) may affect the purity of hydrogen.

Turbo compressor: Turbo compressors work on hydrogen through high-speed rotating impellers, converting its kinetic energy into pressure energy. This type of compressor has the advantages of large flow, smooth operation, and low noise, but it is usually suitable for lower compression ratios and higher flow rates, and has higher requirements for gas cleanliness.

Main sources of energy consumption of hydrogen compressors

The energy consumption of hydrogen compressors is mainly reflected in the following aspects:

Mechanical power consumption: This is the energy required for the compressor to work, which is used to overcome the internal friction and external resistance of hydrogen and increase its pressure to the required level. The power consumption of the ideal compression process is the minimum power consumption calculated according to the principles of thermodynamics, but the actual compression process will be much higher than the ideal value due to various losses.

Friction loss: The friction between the moving parts inside the compressor (such as pistons, connecting rods, bearings, gears, etc.) will produce energy loss and convert it into heat dissipation.

Gas leakage: Poor sealing inside the compressor or at the pipe connection will cause hydrogen leakage, resulting in loss of effective compression volume, thereby indirectly increasing the energy consumption per unit compression volume.

Cooling system energy consumption: Hydrogen will release a lot of heat during the compression process. If it is not dissipated in time, it will cause the gas temperature to rise and reduce the compression efficiency. Therefore, the cooling system is indispensable, but the operation of cooling pumps, fans and other equipment will also consume energy.

Auxiliary equipment energy consumption: In addition to the compressor body, its supporting auxiliary equipment, such as oil pumps, filters, dryers, control systems, etc., also need to consume electrical energy.

Pressure loss: Pipes, valves, filters and other accessories will cause pressure loss, which will cause the compressor to do extra work to reach the target pressure.

Start-stop energy consumption: Frequent start-stop of the compressor will generate additional impact current and mechanical loss, especially under inefficient working conditions.

Key factors affecting energy consumption

The key factors affecting the energy consumption of hydrogen compressors include:

Compression ratio: The higher the compression ratio (the ratio of outlet pressure to inlet pressure), the more work is required and the higher the energy consumption.

Flow rate: Under the same compression ratio, the larger the hydrogen flow rate, the higher the total energy consumption.

Inlet temperature: The higher the inlet temperature, the lower the hydrogen density, the fewer molecules the same volume of gas contains, and a larger compression ratio is required to reach the target pressure, thereby increasing energy consumption.

Cooling efficiency: Effective cooling can reduce the gas temperature during the compression process, improve compression efficiency, and thus reduce energy consumption.

Equipment efficiency: The mechanical efficiency, motor efficiency, and transmission efficiency of the compressor itself will affect the total energy consumption.

Operating conditions: When the compressor deviates from the design operating point, its efficiency usually decreases, resulting in increased energy consumption. For example, compressors operating at low loads are often inefficient.

Maintenance status: Equipment aging, wear, poor sealing, insufficient lubrication, and other problems will lead to reduced compressor efficiency and increased energy consumption.

Strategy 1: Optimize the selection and configuration of compressors

The selection and configuration of hydrogen compressors is the first and most important step in energy conservation. Reasonable selection can not only meet production needs, but also reduce operating costs from the source.

Choose the right type of compressor according to the application scenario

Different application scenarios have different requirements for hydrogen compressors, for example:

Hydrogen refueling stations: usually require high-pressure (35MPa or 70MPa) and variable flow hydrogen supply, with high purity requirements. Diaphragm compressors are widely used in this field due to their oil-free compression characteristics. In addition, ion liquid compressors are also being tried in the field of hydrogen refueling stations.

Industrial hydrogen: For example, in the fields of chemical industry, metallurgy, etc., the range of hydrogen flow and pressure may be wider, and the purity requirements are relatively flexible. Piston compressors or turbo compressors may be more suitable, depending on the specific requirements of flow and pressure.

Hydrogen storage and transportation: Hydrogen needs to be compressed to very high pressure (such as 20MPa to hundreds of MPa) for long-distance transportation or high-density storage. Diaphragm compressors and new ion liquid compressors are the main choices.

Fuel cell testing: The purity requirements of hydrogen are extremely high, and diaphragm compressors or oil-free piston compressors are usually required.

When choosing the type of compressor, it is necessary to comprehensively consider factors such as hydrogen purity requirements, outlet pressure, flow, operation mode (continuous or intermittent), site restrictions, maintenance convenience, and initial investment cost. For example, for fuel cell applications with strict purity requirements, even if the initial investment and maintenance costs of diaphragm compressors are high, the long-term benefits brought by its oil-free compression characteristics (avoiding catalyst poisoning and extending equipment life) may make it a more economical choice.

Accurately match the capacity of the compressor with actual needs

Excessive or small compressor capacity will lead to increased energy consumption.

Excessive capacity: causes the compressor to run at low load or even no load for a long time. The efficiency of many compressors will be significantly reduced under non-full load conditions, resulting in waste of electricity. In addition, the initial investment cost of an oversized compressor is also higher.

Too small capacity: unable to meet production needs, may require long-term overload operation, and even cause equipment failure or frequent shutdown, which affects production continuity and shortens equipment life. In order to make up for the lack of capacity, it may be necessary to purchase new compressors, which increases the total cost.

Therefore, when selecting, a detailed hydrogen demand forecast should be made, including peak flow, average flow, minimum flow, and flow fluctuation. Ideally, the rated capacity of the compressor should be slightly higher than the maximum demand, and a certain margin should be left to cope with future growth or unexpected situations. For occasions with large demand fluctuations, it is possible to consider using multiple small-capacity compressors in parallel, and flexibly start and stop or adjust the load of each compressor according to actual needs to achieve the best operating efficiency.

Optimization design of multi-stage compression and interstage cooling

Hydrogen compression is usually a multi-stage process, that is, the gas is gradually compressed from low pressure to high pressure. Multi-stage compression has significant energy-saving advantages compared to single-stage compression, mainly because:

Reducing exhaust temperature: Single-stage high-pressure compression will cause the exhaust temperature to rise sharply, causing the gas to expand and reduce compression efficiency. Multi-stage compression can effectively control the compression ratio of each stage, thereby reducing the single-stage exhaust temperature.

Improve isothermal efficiency: If a cooler is set between each stage (interstage cooling), the hydrogen that has increased in temperature after the previous stage of compression can be cooled to close to the initial temperature, so that the entire compression process is closer to the ideal isothermal compression. In theory, the power consumption of isothermal compression is minimal.

The design of optimizing interstage cooling includes:

Choice of cooling medium: Water or air is usually used as the cooling medium. Water cooling is more efficient, but a cooling water system is required; air cooling is more convenient, but the cooling efficiency is affected by the ambient temperature.

Cooler type: plate heat exchanger, shell and tube heat exchanger, etc. Select the appropriate cooler type and size to ensure sufficient heat exchange area and efficiency.

Control of cooling temperature: Cool the interstage hydrogen temperature to the lowest possible level, but also avoid problems such as condensation caused by too low temperature, especially for hydrogen containing trace amounts of water vapor.

Control of pressure drop: The interstage cooler will produce a certain pressure loss. While ensuring the cooling effect, the pressure loss should be minimized to reduce additional power consumption.

By optimizing multi-stage compression and interstage cooling, the total energy consumption of the compressor can be significantly reduced. For example, at the same compression ratio, two-stage compression with interstage cooling can save 15%~20% energy than single-stage compression.

Efficient matching of transmission system and motor

The energy consumption of the compressor is ultimately reflected in the power consumption of the drive motor. Therefore, it is crucial to select high-efficiency motors and optimize the transmission system.

Selection of high-efficiency motors: First-level or second-level energy-efficiency motors (such as IE3 or IE4 standards) specified in national energy efficiency standards are preferred, and their energy efficiency is 3%~8% higher than that of ordinary motors. Although the initial investment of high-efficiency motors is slightly higher, the electricity bills saved over the entire life cycle will far exceed the initial cost.

Application of variable frequency drive (VFD): For occasions with large flow fluctuations, using variable frequency drive (VFD) to control the motor speed is an effective means to achieve energy saving. By adjusting the motor speed, the compressor flow can be accurately controlled so that its output matches the actual demand, avoiding the energy waste caused by traditional throttling or unloading methods. The energy-saving effect of variable frequency speed regulation is particularly significant during low-load operation. When the flow rate is reduced by 20%, the use of variable frequency speed regulation can save 30%~50% energy.

Optimization of transmission mode: Common transmission modes include belt drive and direct drive.

Belt drive: The cost is low, but there are energy loss and maintenance problems (belt wear and slippage). Regular inspection and replacement of belts to ensure that the belt tension is moderate can reduce energy loss.

Direct drive: Higher efficiency and less maintenance, but higher installation accuracy requirements. For high-power and long-term compressors, direct drive is a better choice.

Magnetic suspension technology: For some high-end or new compressors, such as centrifugal compressors, magnetic suspension bearing technology can be considered. Magnetic suspension bearings are contactless and frictionless, which can significantly reduce mechanical losses, improve compressor efficiency, and extend equipment life. Although the initial investment is high, its advantages in energy saving and maintenance are very obvious.

Reasonable configuration of auxiliary equipment

In addition to the compressor body, its supporting auxiliary equipment, such as oil pumps, filters, dryers, cooling fans, etc., should also be optimized for energy saving.

High-efficiency cooling fan/pump: Select high-efficiency cooling fans and cooling water pumps to ensure that their flow and head match actual needs. You can consider using variable frequency control to adjust the speed according to cooling needs.

Low pressure drop filter: The filter will produce a certain pressure loss. Select a high-efficiency filter with a lower pressure drop, and clean or replace the filter element regularly to maintain the minimum pressure loss.

Energy saving of adsorption dryer: For occasions where hydrogen needs to be dried, adsorption dryers are commonly used equipment. Traditional adsorption dryers have high regeneration energy consumption. You can consider using more energy-saving regeneration methods such as heatless regeneration, micro-heat regeneration or pressure swing adsorption (PSA). At the same time, optimize the switching cycle of the drying tower and the amount of regeneration gas used to reduce unnecessary energy consumption.

Automated control system: Introduce advanced automated control systems to realize intelligent start and stop, load adjustment, fault diagnosis and energy consumption monitoring of the compressor, reduce manual intervention, and improve operating efficiency. For example, according to the downstream hydrogen demand, automatically adjust the compressor operating parameters to avoid frequent start and stop or no-load operation.

By fully considering energy-saving factors in the compressor selection and configuration stage, a solid foundation can be laid for subsequent operation and maintenance, achieving energy saving from the design source.

Strategy 2: Optimize the temperature control and cooling system during the compression process

During the hydrogen compression process, the increase in gas temperature is inevitable because the compression work will be converted into the internal energy of the gas. However, too high a temperature will not only reduce the compression efficiency and increase energy consumption, but may also have an adverse effect on equipment materials and hydrogen purity. Therefore, optimizing the temperature control and cooling system during the compression process is a key link in achieving energy conservation.

Cooling principle and importance

When hydrogen is compressed, its temperature will increase due to violent collisions between molecules. According to the principles of thermodynamics, the power consumption required for isothermal compression (i.e., the temperature remains unchanged during the compression process) is minimal. Although actual compression cannot be completely isothermal, effective cooling can significantly reduce power consumption by making it close to an isothermal process.

The importance of the cooling system is reflected in:

Improving compression efficiency: Lowering the gas temperature can reduce the gas volume, so that the same mass of hydrogen occupies a smaller space in the compressor, thereby improving the volumetric efficiency and the overall efficiency of the compressor.

Protecting equipment: High temperature will accelerate the wear and aging of equipment components, especially the impact on seals and lubricants. Effective cooling can extend the service life of equipment and reduce maintenance costs.

Ensure hydrogen quality: For some specific applications, such as fuel cells, high-purity hydrogen is essential. High temperature may induce some chemical reactions, affect the purity of hydrogen, and may even cause materials to precipitate and contaminate hydrogen.

Operational safety: High-temperature hydrogen has certain safety risks. Proper cooling helps to maintain the operating temperature within a safe range.

Optimize cooling medium and cooling method

Selecting the right cooling medium and cooling method is crucial to cooling efficiency.

Cooling medium:

Water cooling: Water has a high specific heat capacity and thermal conductivity, good cooling effect, and can take away a lot of heat. A circulating water system is usually used, equipped with a cooling tower or chiller.

Air cooling: Using air as a cooling medium, the structure is relatively simple and no additional water resources are required. However, air cooling is greatly affected by ambient temperature and has relatively low cooling efficiency. It is suitable for areas where cooling effects are not so demanding or water resources are scarce.

Oil cooling: For some oil-lubricated compressors, the lubricating oil itself can also be used as a cooling medium to dissipate heat through an oil cooler.

Cooling method:

Direct contact cooling: The gas is in direct contact with the cooling medium, such as a liquid ring compressor. The advantage is high cooling efficiency, but the cooling medium may contaminate the hydrogen.

Indirect contact cooling (heat exchanger): The gas is not in direct contact with the cooling medium, and heat is exchanged through a heat exchanger. This is currently the most commonly used cooling method for hydrogen compressors, which can ensure the purity of hydrogen.

Optimization suggestions:

Select an efficient heat exchanger: Select a heat exchanger type with a high heat transfer coefficient and low flow resistance, such as a plate heat exchanger, a fin-tube heat exchanger, etc.

Clean the heat exchanger regularly: Scaling or dust accumulation on the surface of the heat exchanger will seriously affect the heat transfer efficiency. Clean and maintain regularly to ensure that the surface of the heat exchanger is clean.

Optimize cooling water/air volume: According to the actual operating conditions and ambient temperature, dynamically adjust the cooling water flow or cooling air volume to avoid overcooling or insufficient cooling, thereby optimizing the energy consumption of the cooling system. For example, frequency conversion can be used to control the cooling water pump and fan so that their speed matches the cooling demand.

Water quality management: For water cooling systems, water quality management should be strengthened to prevent scaling, corrosion and microbial growth, which will reduce heat exchange efficiency.

Refined design of interstage cooling and post-cooling

As mentioned earlier, multi-stage compression and interstage cooling are crucial to energy saving.

Interstage cooling:

Optimize interstage temperature: The goal is to cool the hydrogen temperature after each stage of compression to a level as close to the inlet temperature as possible, usually the ambient temperature or the preset minimum safe temperature. This can minimize the intake volume of the next stage of compression, thereby reducing power consumption.

Pressure drop control: While providing cooling effect, the interstage cooler will produce a certain amount of pressure loss. When designing, the cooling efficiency and pressure loss should be balanced, and a reasonable cooler size and pipeline layout should be selected to minimize the total energy consumption. Excessive pressure drop will offset part of the energy saving effect brought by cooling.

Temperature monitoring and control: Install temperature sensors to monitor the gas temperature after compression at each stage in real time, and automatically adjust the flow of the cooling medium according to the set target temperature to ensure the cooling effect.

Aftercooling:

Necessity: Even after multi-stage compression and inter-stage cooling, the temperature of the final discharged hydrogen may still be high and not suitable for direct storage or use. The function of the aftercooler is to cool the hydrogen at the final discharge pressure to the required storage or use temperature, usually ambient temperature.

Energy recovery: The heat taken away by the aftercooler can be considered for energy recovery, such as for preheating other process fluids or providing low-grade thermal energy, thereby improving the energy efficiency of the entire system. Although the recovered heat does not contribute much to the energy saving of the compressor itself, it can improve the energy efficiency of the entire plant or system.

Waste heat recovery and utilization

The heat generated during the hydrogen compression process is huge. If it can be effectively recovered and utilized, it will significantly improve the comprehensive energy utilization efficiency.

Heat pump technology: Heat pump technology can be used to upgrade the low- and medium-grade waste heat discharged by the compressor to high-grade thermal energy for heating, preheating, drying or other industrial processes.

Waste heat boiler/heat exchanger: The heat generated during the compression process is converted into hot water or steam through a heat exchanger for production or life use.

ORC (Organic Rankine Cycle) Power Generation: For compressors that generate a large amount of medium and high temperature waste heat, the organic Rankine cycle technology can be considered to convert waste heat into electrical energy. Although this technology is not yet popular in hydrogen compressors, there are successful cases in large industrial compressors.

Waste heat recovery and utilization can not only save energy, but also reduce greenhouse gas emissions, with significant environmental benefits.

Optimization of pipelines and valves

Irrational design of pipelines and valves will also lead to pressure loss and increased energy consumption.

Pipeline size optimization: Too small inner diameter of the pipeline will lead to too high flow rate, generate greater friction resistance, and increase pressure loss. By optimizing the pipeline size, ensure that the flow rate is within a reasonable range and reduce the pressure drop.

Reduce elbows and valves: elbows, valves, reducers and other pipe fittings will cause local pressure loss. When designing the pipeline system, unnecessary elbows and valves should be minimized, and valve types with low flow resistance should be selected.

Insulation measures: For high-pressure or low-temperature hydrogen pipelines, good insulation should be carried out to reduce heat exchange with the environment and maintain a stable gas temperature, thereby avoiding additional cooling or heating requirements.

By fully optimizing the temperature control and cooling system, the compression process can be ensured to be carried out efficiently, thermodynamic losses can be minimized, and significant energy saving effects can be achieved.

Strategy 3: Improve the load management and operating efficiency of the compressor

Even if an efficient compressor is selected and the cooling system is optimized, if the daily operation management is improper, it may lead to huge energy waste. Effective load management and refined operation are the key to continuous energy saving.

Avoid no-load and frequent start-stop

The harm of no-load operation: Many compressors still consume a lot of electrical energy in the no-load state to overcome mechanical friction, wind resistance and maintain the operation of auxiliary equipment. Although there is no effective compression, the energy consumption may reach 20%~40% of the full load.

The harm of frequent start-stop: Each time the compressor starts, a large starting current will be generated, which will impact the power grid and accelerate the wear of the motor and mechanical parts. Frequent start-stop also means that the system pressure fluctuates greatly and is difficult to maintain stability.

Optimization suggestions:

Pressure band control: Set reasonable upper and lower pressure bands. When the system pressure reaches the upper limit, the compressor is unloaded or shut down; when the pressure drops to the lower limit, the compressor is loaded and operated. The width of the pressure band needs to be optimized according to actual needs and system response speed. Too narrow will lead to frequent start and stop, while too wide may cause excessive pressure fluctuations.

Gas tank optimization: Reasonably configure the volume of the gas tank. The gas tank can smooth pressure fluctuations and reduce the number of starts and stops of the compressor. When the gas consumption is temporarily greater than the gas supply of the compressor, it is replenished by the gas tank; when the gas consumption is temporarily less than the gas supply, the excess gas is stored in the gas tank.

Optimize the start-stop logic: For systems with multiple compressors running in parallel, intelligent start-stop and load-unload logic should be designed. For example, a prediction-based control strategy can be adopted to start or stop the compressor in advance based on historical gas consumption data and real-time demand to avoid lag.

Sleep mode: For some compressors with sleep function, when they are not needed for a long time, they can enter deep sleep mode, shut down most auxiliary equipment, and minimize energy consumption.

Accurately control the outlet pressure

In many cases, the outlet pressure of the compressor is set higher than the actual requirement to cope with fluctuations in gas consumption or pipeline losses. However, every increase of 0.1MPa in outlet pressure usually increases power consumption by 1%~3%.

Optimization suggestions:

Accurate demand analysis: Accurately evaluate the minimum pressure requirements of downstream hydrogen-using equipment or processes, and set a reasonable compressor outlet pressure on this basis.

Pressure sensor and feedback control: Install high-precision pressure sensors to monitor outlet pressure in real time, and use advanced control algorithms such as PID (proportional-integral-differential) controllers to achieve precise regulation of compressor output pressure.

Optimize pipeline layout: Reduce pressure loss caused by pipeline length, elbows, valves, filters and other accessories, thereby reducing the outlet pressure required by the compressor.

Variable frequency speed regulation and intelligent control

Variable frequency speed regulation technology is revolutionary in the field of compressor energy saving.

Advantages of variable frequency speed regulation: As mentioned above, the compressor flow is changed by adjusting the motor speed to accurately match the actual gas demand. When the gas consumption decreases, the speed is reduced, and the energy consumption decreases in a cubic relationship (energy consumption is proportional to the cube of the speed). This is more energy-saving than traditional unloading or bypass control methods.

Multi-machine joint control: For systems with multiple compressors, a central control system is used to achieve multi-machine joint control. The system intelligently distributes the load based on real-time gas consumption, the efficiency curve of each compressor, operating time and other factors, so that all compressors operate at the highest efficiency point or high-efficiency range. For example, the principle of “start first and stop later, start later and stop first” or the principle of “selecting the operating unit according to the efficiency curve” can be adopted.

Predictive control: Combine production plans and historical data to predict future gas demand, adjust the compressor operating status in advance, and avoid energy waste caused by delayed response.

Remote monitoring and diagnosis: Establish a remote monitoring platform to monitor the compressor operating data (flow, pressure, temperature, current, voltage, vibration, etc.) in real time, detect abnormalities and diagnose them in time, provide data support for maintenance, and avoid unplanned downtime and unnecessary energy consumption.

Gas leak detection and repair

Hydrogen leakage not only brings safety hazards, but also huge energy waste.

Identification of leak points: Regularly use professional hydrogen leak detectors or foam solutions for inspection, especially in flange connections, valves, seals, pipeline welding and other parts prone to leakage.

Timely repair: Once a leak is found, it should be repaired immediately. Even a small leak can cause considerable energy loss if accumulated over a long period of time.

Preventive maintenance: In daily maintenance, pay attention to the inspection and replacement of wearing parts such as seals, gaskets, and valve packings to reduce the occurrence of leaks at the source.

Process optimization

In some hydrogen application scenarios, the demand for compressors can be reduced by optimizing the upstream or downstream process flow, thereby achieving indirect energy saving.

Utilize upstream residual pressure: If the upstream process can provide hydrogen at a certain pressure, there is no need to completely reduce the hydrogen to normal pressure before compressing it. The residual pressure can be directly used to enter the compressor to reduce the compression ratio.

Demand-side management: Encourage downstream hydrogen users to use hydrogen during non-peak hours, flatten the gas consumption curve, and reduce the demand for peak load of the compressor.

Hydrogen recovery and utilization: For low-pressure hydrogen tail gas generated in some processes, if the purity allows, it can be considered for recovery and utilization, such as returning it to the process through a booster fan or a small compressor instead of directly discharging it.

Through refined load management and intelligent operation, the energy-saving potential of hydrogen compressors can be maximized, so that they can always remain in the high-efficiency range in actual operation, thereby significantly reducing operating costs.

Summary

Energy saving of hydrogen compressors is a systematic project, which requires comprehensive consideration and continuous optimization from multiple levels such as equipment selection, system design, operation management to technological innovation. By adopting the five strategies proposed in this article and implementing them in the full life cycle management of hydrogen compressor projects, enterprises can not only significantly reduce operating costs and improve the economic competitiveness of hydrogen energy, but also contribute to the realization of clean energy transformation and sustainable development. With the continuous advancement of technology, hydrogen compressors in the future will be more intelligent and efficient, and play a greater role in building a zero-carbon society.